Transport for Some?

Mobility in East LondonContext

Tottenham Court Road was where I first saw TfL’s “Fabric of London” campaign via a digital art installation at Outernet that told the stories of a diverse group of Londoners living in the city.

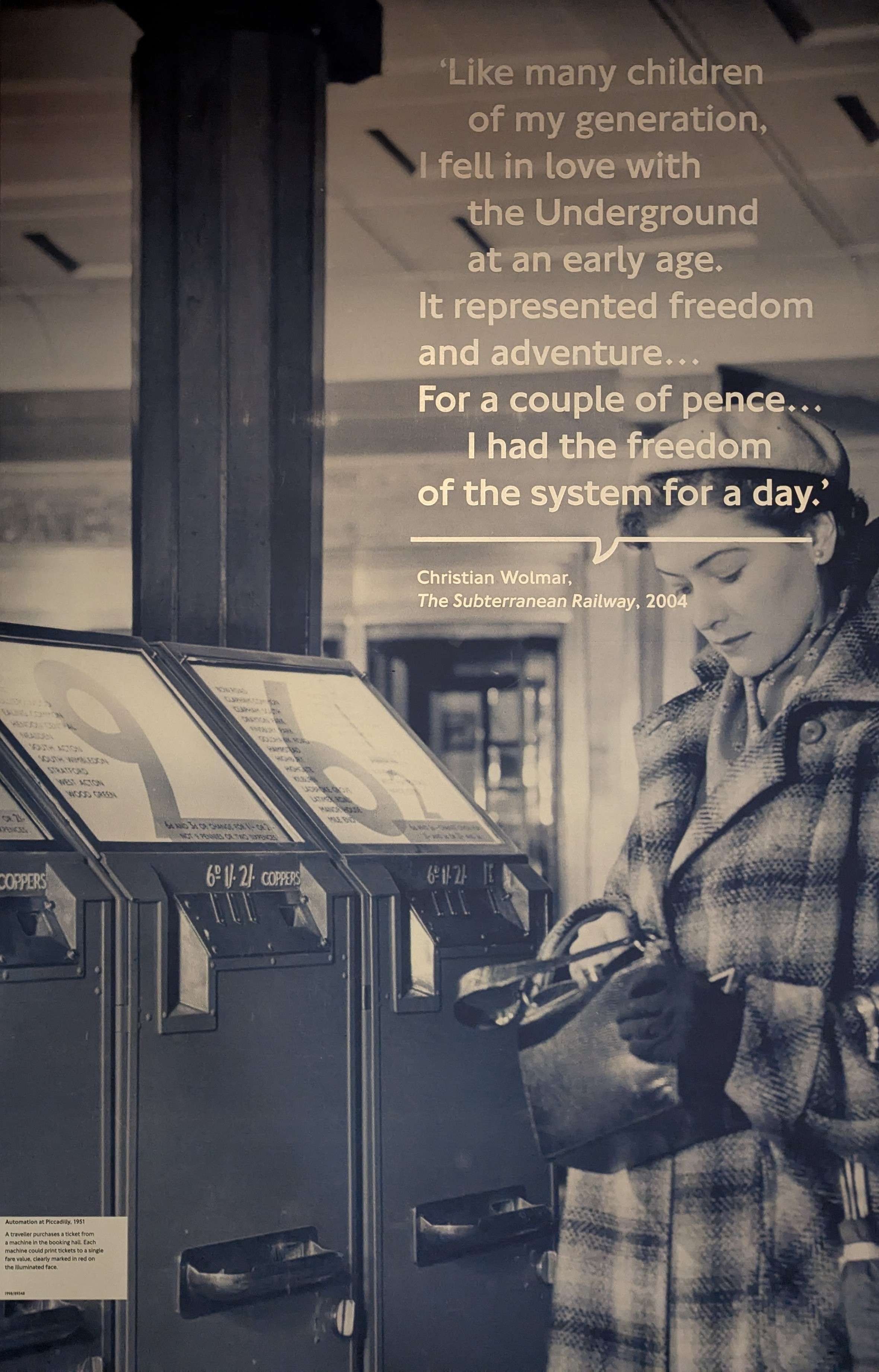

The piece lived rent-free in my mind ever since. TfL is perhaps the single most iconic thing in London, with the city (and myself) being unrecognisable had it not existed. Public transport in London means as many different things as there are people here, and as much as we grumble about it, we all rely on it to live our lives; London is one of only a few places in the UK where access to a private automobile is not a pre-requisite for participating in society to the fullest. For myself and many others that grew up in London, the Tube is often viewed with the same sense of freedom and independence that other places associate with getting their first car as a teenager.

The benefits of public transport (or more accurately, viable alternatives to driving) are widely understood.

It results in massively better health outcomes — not just because of reduced air pollution, but also due to increased physical activity:

For the [London 2030 forecasted] increased active travel and sustainable transport scenarios, [...] compared with [a year of] business as usual, the lower-carbon-emission motor vehicles scenario saved 160 DALYs and 17 premature deaths per million population, increased active travel saved 7332 DALYs and 530 premature deaths per million population, and the towards sustainable transport scenario saved 7439 DALYs and 541 premature deaths per million population.Public health benefits of strategies to reduce greenhouse-gas emissions: urban land transport, Woodcock et al. 2009

It is also excellent for the economy, with areas served by public transport seeing more new businesses compared to car-dependent areas:

when compared to automobile-adjacent areas, proximity to the light rail significantly increases new business starts in the three industries of interest: retail, services and knowledge. Even when controlling for a variety of factors – including location in a downtown business district – adjacency to light rail stations is worth about 88% additional new starts in the knowledge sector, 40% new starts in the service sector and 28% new starts in the retail sector over the time that the line has been open.Transit-oriented economic development: The impact of light rail on new business starts in the Phoenix, AZ, Credit, 2017

However, at a local and individual level, is the picture the same?

How has transport in East London served the people that live there?

Transit-oriented development

Transit oriented development is an urban planning concept that uses public transport as the focus of growing urban areas. East London has benefitted massively from this, with Canary Wharf being the poster child of this.

From The Isle of Dogs Before the Big Money, Seaborne, Hoxton Mini Press

Photographs of the Isle of Dogs in the 1980s are almost completely unrecognisable to the area today. A core part of the transformation was driven by the construction of the DLR, and the Jubilee Line Extension (JLE).

It regenerated the local area and significantly increased employment nearby, which was a big deal for somewhere that was in continual decline due to the decline of the docks.

There was an increase in employment at twice the London rate across all station catchment areas in aggregate in the 1-year ‘before and after opening’ period. This was 5600 higher in terms of jobs than it would have been had it grown at the average rate for London as a whole.Public transport investment and local regeneration: A comparison of London׳s Jubilee Line Extension and the Madrid Metrosur, Mejia-Dorantes, 2014

However, the same paper also acknowledges that these benefits were not spread evenly:

There were only three catchments that did not grow at above the London average: the Southwark catchment area, which was already quite densely developed and already had good public transport access; the North Greenwich catchment area, where activity was directly related to the as yet undeveloped Millennium Dome; and the West Ham catchment area, which was predominantly an area of social housing with little development opportunity. [...] Not surprisingly, given that the JLE was specifically designed to support increased employment activity in the new Canary Wharf financial district, the greatest percentage of employers reporting increases in employment were in this catchment area. Canning Town in the more run-down East of London appeared largely unaffected by the JLE opening, with three quarters of the sample reporting employment to be broadly the same as before the opening of the JLE.Public transport investment and local regeneration: A comparison of London׳s Jubilee Line Extension and the Madrid Metrosur, Mejia-Dorantes, 2014

Inequality is unfortunately a common thread through a lot of East London’s redevelopment. Many areas have improved immensely, but it has in some places also emphasised class divides. The most striking example I found during my visits was Stratford station.

One side of Stratford exits onto the modern Westfield shopping centre with highrise new-build apartments, while the other exit leads to a busy road with a run-down shopping centre, and older buildings covered in graffiti. This is a scene that can be seen across a lot of East London, including Hackney, where I grew up. The original residents of an area are often priced out when new development occurs, or do not experience the same transformational benefits as new residents.

A 2019 paper by Cao that shows that being near a station alone is not inherently equitable; rather, different demographics are able to take advantage of the ‘capabilities’ offered, with more privileged groups (i.e. white affluent men) benefitting the most. The paper notes a variety of potential reasons for this, such as individual safety, ability to pay for the costs of transport, or being qualified for higher paying jobs that can be commuted to.

This seems to also have been reflected in observations made by myself while using these services; regardless of the time of day, people using the Jubilee line often appeared to be more white and more affluently dressed compared to what the demographics of East London would suggest.

However, the same paper also interestingly found that the incoming residents had worse ‘capabilities’ than the original residents, suggesting that the issue is more complex than just “gentrification prices people out”.

Urban transport and social inequities in neighbourhoods near underground stations in Greater London, Cao, 2019The incumbent population (those who lived in the Underground station catchment areas before the JLE was built) (Column E) were more likely to score higher, for capabilities and functionings, relative to incomers. This finding is contrary to those of previous studies (e.g. Jones 2015; Lane et al. 2004), in which it was found that incomers gained most benefit from the JLE, certainly in terms of access to employment. There may be a number of reasons for this; perhaps the most recent incomers have to spend a large proportion of their household budget on rent, hence there may be a generational issue in participating in activities. Another possible explanation could be that some members of the incumbent population are people who chose to re-locate to the station catchment areas because they were aware that the metro would be opening soon (i.e. they were really in-movers but were still categorised as belonging to one of the types of incumbent residents due to the fact that they moved in before the metro opened). This is an issue that requires further exploration.

Capability to benefit from transport

Regardless, the paper does correctly highlight that geographical access to transport is not the only factor in determining whether an individual can take advantage of it.

London’s transport system is notoriously inaccessible, in every sense of the word.

Few stations have step-free access, excluding many people that can’t negotiate stairs or those that find it difficult to cross large gaps.

Many of the least accessible stations are in major employment centres, such as the above photograph taken on the Central Line platform at Bank.

The system is also difficult to use for those with sensory difficulties: for example, trains are frequently loud enough to cause permanent hearing damage.

Fares are also a barrier to access. TfL’s fares are very high compared to other cities. One potential factor is that TfL receives an unusually low amount of funding for a public transit agency, with fares expected to cover most of their expenses, which are also likely to be higher than many other cities with more modern and more reliable infrastructure. TfL’s farebox recovery ratio for the Tube (the amount of revenue made by fares relative to the costs of running the service) is above 100%.

All these factors combined create a system where the most marginalised in society often gain the least from public transport. East London is one of the most deprived areas in London, as well as the most ethnically diverse.

The Silvertown Tunnel

Saying that the opening of the Silvertown Tunnel was controversial is quite the understatement. Many feel that it further entrenches inequality due to the introduction of tolls on both the new tunnel and the existing Blackwall Tunnel right beside it. Perhaps the most confusing part of the project is that the off-peak toll of £1.50 is actually cheaper than the cost of all public transport options that cross the river, which raises questions about whether the purpose of the toll is truly to reduce congestion.

It is widely understood in transport and urban planning circles that building new roads will not reduce traffic, but instead induces additional demand. If driving becomes more attractive, more people will choose to make their journey by car, cancelling out the added capacity and bringing more cars onto the road.

In a part of London that is desperately in need of more accessible (in every sense) ways to cross the Thames, the Silvertown Tunnel seems like a mistake, especially because it encourages more car use while simultaneously making previously existing journeys more expensive.

Conclusion

London has made great strides in improving public transport, as well as using it as a catalyst for urban regeneration. However, the benefits of this haven’t been equally distributed. More investment and research is needed to ensure that future transport projects are equitable to all East Londoners. The Docklands is the main example of this, but similar patterns are also seen across other areas of East London, including Stratford.

Potential future research

This has mostly focused on how the impacts of TfL operated rail services in East London. There are many other modes of public transport that were not discussed here but are important to consider, such as bus services and ferries. Additionally, the Elizabeth Line is another example of major transport investment resulting in significant change to the areas it serves, and is worth exploring to confirm if similar patterns are seen in other areas of London.